In celebration of the first 25 years of this century, the New York Times surveyed hundreds of novelists, nonfiction writers, poets, critics, and other book lovers, asking them to name the 10 best books that have been published since January 1, 2000. The resulting list of “The 100 Best Books of the 21st Century” is a dazzling celebration of contemporary voices, including 15 of our speakers. Browse the books voted “best in the century” below.

The New York Times‘s 100 Best Books of the Century

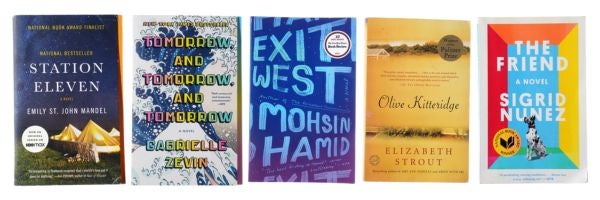

93: Station Eleven – Emily St. James Mandel

Increasingly, and for obvious reasons, end-times novels are not hard to find. But few have conjured the strange luck of surviving an apocalypse — civilization preserved via the ad hoc Shakespeare of a traveling theater troupe; entire human ecosystems contained in an abandoned airport — with as much spooky melancholic beauty as Mandel does in her beguiling fourth novel. (Voted for by Ann Napolitano)

76: Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow – Gabrielle Zevin

The title is Shakespeare; the terrain, more or less, is video games. Neither of those bare facts telegraphs the emotional and narrative breadth of Zevin’s breakout novel, her fifth for adults. As the childhood friendship between two future game-makers blooms into a rich creative collaboration and, later, alienation, the book becomes a dazzling disquisition on art, ambition and the endurance of platonic love.

75: Exit West – Mohsin Hamid

The modern world and all its issues can feel heavy — too heavy for the fancies of fiction. Hamid’s quietly luminous novel, about a pair of lovers in a war-ravaged Middle Eastern country who find that certain doors can open portals, literally, to other lands, works in a kind of minor-key magical realism that bears its weight beautifully. (Voted for by Gary Shteyngart)

74: Olive Kitteridge – Elizabeth Strout

When this novel-in-stories won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 2009, it was a victory for crotchety, unapologetic women everywhere, especially ones who weren’t, as Olive herself might have put it, spring chickens. The patron saint of plain-spokenness — and the titular character of Strout’s 13 tales — is a long-married Mainer with regrets, hopes and a lobster boat’s worth of quiet empathy. Her small-town travails instantly became stand-ins for something much bigger, even universal. (Voted for by Nick Hornby)

68: The Friend – Sigrid Nunez

After suffering the loss of an old friend and adopting his Great Dane, the book’s heroine muses on death, friendship, and the gifts and burdens of a literary life. Out of these fragments a philosophy of grief springs like a rabbit out of a hat; Nunez is a magician. — Ada Calhoun, author of Also a Poet: Frank O’Hara, My Father, and Me

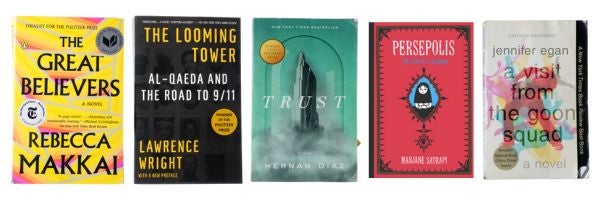

64: The Great Believers – Rebecca Makkai

It’s mid-1980s Chicago, and young men — beautiful, recalcitrant boys, full of promise and pure life force — are dying, felled by a strange virus. Makkai’s recounting of a circle of friends who die one by one, interspersed with a circa-2015 Parisian subplot, is indubitably an AIDS story, but one that skirts po-faced solemnity and cliché at nearly every turn: a bighearted, deeply generous book whose resonance echoes across decades of loss and liberation.

55: The Looming Tower – Lawrence Wright

What happened in New York City one incongruously sunny morning in September was never, of course, the product of some spontaneous plan. Wright’s meticulous history operates as a sort of panopticon on the events leading up to that fateful day, spanning more than five decades and a geopolitical guest list that includes everyone from the counterterrorism chief of the F.B.I. to the anonymous foot soldiers of Al Qaeda.

50: Trust – Hernan Diaz

How many ways can you tell the same story? Which one is true? These questions and their ethical implications hover over Diaz’s second novel. It starts out as a tale of wealth and power in 1920s New York — something Theodore Dreiser or Edith Wharton might have taken up — and leaps forward in time, across the boroughs and down the social ladder, breathing new vitality into the weary tropes of historical fiction. — A.O. Scott

68: Persepolis – Marjane Satrapi

Drawn in stark black-and-white panels, Satrapi’s graphic novel is a moving account of her early life in Iran during the Islamic Revolution and her formative years abroad in Europe. Devastating — but also formally inventive, inspiring and often funny — Persepoli” is a model of visual storytelling and personal narrative.

39: A Visit from the Goon Squad – Jennifer Egan

In the good old pre-digital days, artists used to cram 15 or 20 two-and-a-half-minute songs onto a single vinyl LP. Egan accomplished a similar feat of compression in this Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, a compact, chronologically splintered rock opera with (as they say nowadays) no skips. The 13 linked stories jump from past to present to future while reshuffling a handful of vivid characters. The themes are mighty but the mood is funny, wistful and intimate, as startling and familiar as your favorite pop album. — A.O. Scott

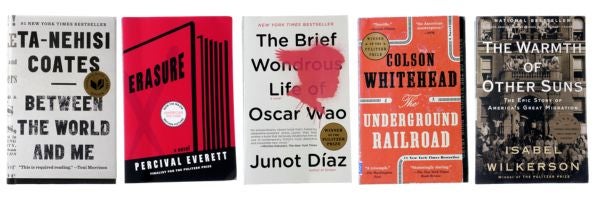

36: Between the World and Me – Ta-Nehisi Coates

Framed, like James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, as both instruction and warning to a young relative on “how one should live within a Black body,” Coates’s book-length letter to his 15-year-old son lands like forked lightning. In pages suffused with both fury and tenderness, his memoir-manifesto delineates a world in which the political remains mortally, maddeningly inseparable from the personal. (Voted for by Bonnie Garmus)

20: Erasure – Percival Everett

More than 20 years before it was made into an Oscar-winning movie, Everett’s deft literary satire imagined a world in which a cerebral novelist and professor named Thelonious “Monk” Ellison finds mainstream success only when he deigns to produce the most broad and ghettoized portrayal of Black pain. If only the ensuing decades had made the whole concept feel laughably obsolete; alas, all the 2023 screen adaptation merited was a title change: American Fiction. (Voted for by Jonathan Lethem)

11: The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao – Junot Díaz

Díaz’s first novel landed like a meteorite in 2007, dazzling critics and prize juries with its mix of Dominican history, coming-of-age tale, comic-book tropes, Tolkien geekery and Spanglish slang. The central plotline follows the nerdy, overweight Oscar de León through childhood, college and a stint in the Dominican Republic, where he falls disastrously in love. Sharply rendered set pieces abound, but the real draw is the author’s voice: brainy yet inviting, mordantly funny, sui generis. (Voted for by Ann Napolitano)

7: The Underground Railroad – Colson Whitehead

“I could hardly make it through this plaintively brutal novel. Neither could I put it down. The Underground Railroad bleeds truth in a way that few treatments of slavery can, fiction or nonfiction. Whitehead’s portrayals of human motivation, interaction and emotional range astonish in their complexity. Here brutality is bone deep and vulnerability is ocean wide, yet bravery and hope shine through in Cora’s insistence on escape.” — Tiya Miles, author of “All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake

2: The Warmth of Other Suns – Isabel Wilkerson

Wilkerson’s intimate, stirring, meticulously researched and myth-dispelling book, which details the Great Migration of Black Americans from South to North and West from 1915 to 1970, is the most vital and compulsively readable work of history in recent memory. This migration, she writes, “would become perhaps the biggest underreported story of the 20th century. It was vast. It was leaderless. It crept along so many thousands of currents over so long a stretch of time as to be difficult for the press truly to capture while it was under way.” Wilkerson blends the stories of individual men and women with a masterful grasp of the big picture, and a great deal of literary finesse. The Warmth of Other Suns reads like a novel. It bears down on the reader like a locomotive. — Dwight Garner (Voted for by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers)